Bo shuda! Today we conclude our very special two-part interview that was months in the making. It's Part 2 of our interview with Jabba the Hutt! Well, not exactly, but it's the closest we could get. Chris and I were able to chat with a few of the amazingly talented puppeteers and sculptors that brought everyone's favorite loathsome slug to life in Return of the Jedi nearly thirty years ago. John Coppinger, Dave Barclay, and Toby Philpott have given us this incredible behind-the-scenes look at what went on inside the belly of the beast during the filming of Return of the Jedi and given us all the slimy details about how one of the most popular villains in film history was created. Here's Part 2. Enjoy!

Also, click here to check out Part 1 if you need to catch up first.

Also, click here to check out Part 1 if you need to catch up first.

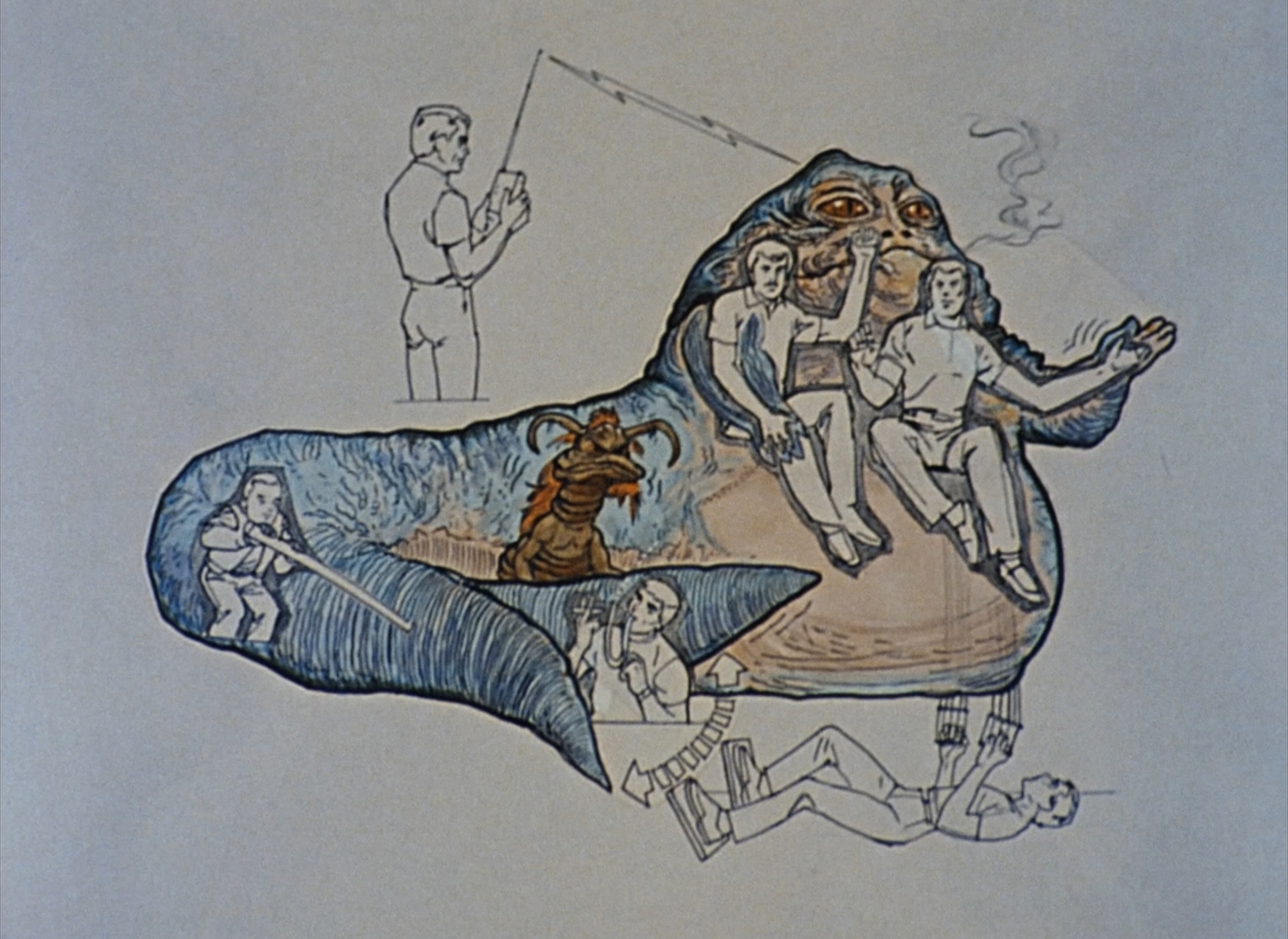

John Coppinger and the Jabba design team. (Image from Muppet Wiki)

Echo Base News: To what extent was George Lucas involved in the process of bringing Jabba to life? What kind of feedback did he give you?

Toby Philpott: Apparently (when they shot the sequence with Declan Mulholland for A New Hope) George conceived of Jabba as some kind of hairy creature – and the plan was to overlay Declan’s performance with a stop-motion animation, but the technology (or the budget) wasn’t up to it at the time. So Jabba had been mentioned in the storyline but not fully envisioned.

I still haven’t found out how come George went to Jim Henson (more famous for cartoon-like Sesame Street and Muppets creatures) to make Yoda (a realistic animatronic puppet). That original idea seems to come out of the blue! Jim then made The Dark Crystal, which formed a showcase of what was possible with those techniques, so the creation of Jabba in his ROTJ incarnation maybe came out of those experiments.

I think George was more closely involved with Phil Tippett’s original conceiving of Jabba, by assessing a variety of maquettes (miniature sculpts). Once the approved model was passed on to Stuart Freeborn’s team I don’t know how much time George spent checking up on them. I have heard rumours that George was not entirely satisfied with Jabba, but Richard Marquand seemed very pleased with the end result, and our performance.

As Dave, Mike and I spent our days inside Jabba we didn’t witness any interactions on the days George was on the set. Perhaps John can tell us more.

John Coppinger: I don't remember George Lucas visiting either workshop while we built Jabba (we sculpted him in the make-up department then moved to a larger shed to assemble him). David Tomblin (1st Assistant Director) did visit to check him out, and so did the guys from ILM once they were set up in Elstree Studios. I made colour sketches of Jabba to show George and Norman Reynolds (Production Designer) in the Art Department, so we did meet him there - I'd done some rubbish ones deliberately, and put the good one, the one we favoured, further down the pile. My devious move worked and they chose our preferred colour! George Lucas did visit with Norman Reynolds when we were assembling Jabba on set and I was painting him. George was quiet and reserved, as he's been characterised, but I do remember a brief conversation. The gist of it was that the money men just wanted him to carry on making Star Wars films while he had some other projects in mind! I think I heard those rumours that George wasn't totally happy with Jabba, but the best compliment any of us will ever get came from David Tomblin one day on set. He stomped past three of us, bull horn in hand, and muttered "You did a good job on that thing"; gesturing back over his shoulder as he swept us aside!

I guess George Lucas visited the set but I only remember talking there with Richard Marquand and David Tomblin. I was somewhat in awe of David; his attention to detail was astounding. When Luke falls into the pit Jabba looks down at him - but with everything at maximum lean he still wasn't far enough forward. David asked me what would happen if two props men pushed him from behind. I said the body would probably fall off its suspension springs and there was a danger the belly air-bag would be burst. He'd been into our workshop just once; but remembered and understood what I was talking about. He took the risk, the body jumped off the springs but the air-bag survived. I knew we could trust David not to blame us - I'm sure if the air-bag had failed he'd have got us stuffing old newspapers into the belly so we could carry on till the end of the day!

I still haven’t found out how come George went to Jim Henson (more famous for cartoon-like Sesame Street and Muppets creatures) to make Yoda (a realistic animatronic puppet). That original idea seems to come out of the blue! Jim then made The Dark Crystal, which formed a showcase of what was possible with those techniques, so the creation of Jabba in his ROTJ incarnation maybe came out of those experiments.

I think George was more closely involved with Phil Tippett’s original conceiving of Jabba, by assessing a variety of maquettes (miniature sculpts). Once the approved model was passed on to Stuart Freeborn’s team I don’t know how much time George spent checking up on them. I have heard rumours that George was not entirely satisfied with Jabba, but Richard Marquand seemed very pleased with the end result, and our performance.

As Dave, Mike and I spent our days inside Jabba we didn’t witness any interactions on the days George was on the set. Perhaps John can tell us more.

John Coppinger: I don't remember George Lucas visiting either workshop while we built Jabba (we sculpted him in the make-up department then moved to a larger shed to assemble him). David Tomblin (1st Assistant Director) did visit to check him out, and so did the guys from ILM once they were set up in Elstree Studios. I made colour sketches of Jabba to show George and Norman Reynolds (Production Designer) in the Art Department, so we did meet him there - I'd done some rubbish ones deliberately, and put the good one, the one we favoured, further down the pile. My devious move worked and they chose our preferred colour! George Lucas did visit with Norman Reynolds when we were assembling Jabba on set and I was painting him. George was quiet and reserved, as he's been characterised, but I do remember a brief conversation. The gist of it was that the money men just wanted him to carry on making Star Wars films while he had some other projects in mind! I think I heard those rumours that George wasn't totally happy with Jabba, but the best compliment any of us will ever get came from David Tomblin one day on set. He stomped past three of us, bull horn in hand, and muttered "You did a good job on that thing"; gesturing back over his shoulder as he swept us aside!

I guess George Lucas visited the set but I only remember talking there with Richard Marquand and David Tomblin. I was somewhat in awe of David; his attention to detail was astounding. When Luke falls into the pit Jabba looks down at him - but with everything at maximum lean he still wasn't far enough forward. David asked me what would happen if two props men pushed him from behind. I said the body would probably fall off its suspension springs and there was a danger the belly air-bag would be burst. He'd been into our workshop just once; but remembered and understood what I was talking about. He took the risk, the body jumped off the springs but the air-bag survived. I knew we could trust David not to blame us - I'm sure if the air-bag had failed he'd have got us stuffing old newspapers into the belly so we could carry on till the end of the day!

Dave Barclay: We started the first few days of filming without George. Director Richard Marquand really liked what we were doing with the performance and told George that when he caught up with the Jabba shoot. George directed second unit and we had a few Jabba shots with George. He was very straightforward and the scenes went very smoothly.

Echo Base News: What was it like inside of Jabba?

Dave Barclay: Initially dark and stuffy, but we got an air conditioning feed to pipe in air for us, which froze us at first, but with adjustments we got the air flow and temperature just right. We had small 4" monitors hung around our necks so we could see what the camera was seeing. I had a microphone for delivering the lines, and we had ear pieces so we could hear the actors on the set. Very quickly it became "home."

John Coppinger: I can only speak from the development phase - We obviously jumped in and out of Jabba's unskinned body as we built and tested him. Tried to break him and modified or strengthened anything that might fail on set. I knew the way in on set was going to be from up and under from a hole in the rostrum lining up with the throne base; but when the throne moved forwards the folks inside might be trapped. So I pre-cut an escape panel into the back of Jabba’s internal body shape. The performers could have kicked their way out from under his brain in an emergency! In fact there was a moment when a fire effect (Luke firing his weapon upwards as he falls into the pit) rained fire and sparks down in front of Jabba. It looked like Tim Rose, operating Salacious Crumb, might have a problem but one of the prop guys ran in with a fire extinguisher just in time. Jabba's arms were sculpted onto casts of my own arms, so I did test the arm gloves. And they were hot and uncomfortable, so yet again I crave forgiveness from Toby and Dave! Otherwise this question has to be passed to the inside crew…

Toby Philpott: You have to understand that Jabba was solid, so rather than think of us wearing a costume (when people ask if it was hot) it’s better to imagine the two of us climbing into a very small cave. And sometimes, a sort of 3-man submarine (as Mike Edmonds had a small place at the back, with a primitive monitor to see what he was doing, when operating the tail for wide shots).

Nowadays we could have miniature cameras all over the place, and monitors on special glasses or headsets, no doubt, as everything is miniaturised now. And we had been a little spoiled on the The Dark Crystal, as the directors and all the main performers were puppeteers who had finessed their technology and set-building around puppets, so we had monitors everywhere, offering a full-colour through-the-lens shot (so you knew exactly where your character was in the frame).

On ROTJ we did not have the luxury of through-the-lens, and simply had a static camera high in the palace, showing us Jabba himself. Useful for basic orientation, but not for detailed work, or knowing whether we were in a wide shot or a close-up. Mike’s monitor was a fair size, but Dave and I had heavy packs hanging round our necks, with about a four-inch square, grainy black and white image. And then we had headsets, with mike and earphone. As a team we could talk to each other, but we mostly maintained radio silence as it could turn into bedlam. Whoever was on the set (often John) would feedback to us what the shot was, how long it might take to set-up, etc, and relay any problems we had to the outside crew. We had coached the director to talk to Jabba as a complete actor (not a set of bits), however, so Dave also needed the channel free to actually speak as Jabba. During the scenes he was doing all the dialogue in English, through speakers, too.

It’s lucky that Dave and I are pretty calm, contemplative guys, because we spent a fair amount of time in there on our own, just waiting, or doing a little practice (if no-one had asked us to pose for lighting, etc.) For wider shots, Mike Edmonds would join us, and he’s a funny guy, so we would brighten up a bit, and time would pass quicker.

So, inside Jabba? Cramped, a bit uncomfortable. Not quite knowing what is going on. Bored with the waiting, alternating with the tension and stage-fright when Dave Tomblin would say “Stand-by”...and then we would hear the word “Action!” and off we would go, mind-melded into Jabba, and doing a take that, if it was the good one, would be on film forever! No pressure, then! Of course, with filming it is possible to do more takes to get it right, but nobody wants to be the person who messes up. You could have 150 people around the set hoping you get it right, so we could all move onto the next thing!

On ROTJ we did not have the luxury of through-the-lens, and simply had a static camera high in the palace, showing us Jabba himself. Useful for basic orientation, but not for detailed work, or knowing whether we were in a wide shot or a close-up. Mike’s monitor was a fair size, but Dave and I had heavy packs hanging round our necks, with about a four-inch square, grainy black and white image. And then we had headsets, with mike and earphone. As a team we could talk to each other, but we mostly maintained radio silence as it could turn into bedlam. Whoever was on the set (often John) would feedback to us what the shot was, how long it might take to set-up, etc, and relay any problems we had to the outside crew. We had coached the director to talk to Jabba as a complete actor (not a set of bits), however, so Dave also needed the channel free to actually speak as Jabba. During the scenes he was doing all the dialogue in English, through speakers, too.

It’s lucky that Dave and I are pretty calm, contemplative guys, because we spent a fair amount of time in there on our own, just waiting, or doing a little practice (if no-one had asked us to pose for lighting, etc.) For wider shots, Mike Edmonds would join us, and he’s a funny guy, so we would brighten up a bit, and time would pass quicker.

So, inside Jabba? Cramped, a bit uncomfortable. Not quite knowing what is going on. Bored with the waiting, alternating with the tension and stage-fright when Dave Tomblin would say “Stand-by”...and then we would hear the word “Action!” and off we would go, mind-melded into Jabba, and doing a take that, if it was the good one, would be on film forever! No pressure, then! Of course, with filming it is possible to do more takes to get it right, but nobody wants to be the person who messes up. You could have 150 people around the set hoping you get it right, so we could all move onto the next thing!

Echo Base News: You've discussed a few already, but what were some difficulties you encountered throughout the process?

Dave Barclay: Generally it all went pretty smoothly. Initially we were having issues getting a decent camera feed to our monitors, so we ended up with a wild camera in the lighting rig, so we could always see what Jabba was doing. In the main palace room, we were able to get inside Jabba by climbing under the set and up through a hole in his plinth. Towards the end of the shoot, when Jabba was on the barge, an entrance through the back of his body was cut to allow us to get in and out. Almost at the last shot, his fiberglass body form cracked and was actually held together by hand by Mike Osborn.

Toby Philpott: The design and support crew had built him well, so we didn’t have any real technical problems, to speak of. For us the problems arose from requests from the director – for instance, Jabba’s hands don’t meet in the middle, so he can’t pass things from hand to hand. The director asked if we could maybe toss something (like the frog) from hand to hand. We tried, but no! For things like pulling the dancing girls’ chains we did some hand-over-hand rehearsing outside, because we didn’t want to hurt the performers, but we really could not see anything much of what we were doing. Likewise (for me) hitting C-3PO, or grabbing Bib Fortuna – all made difficult by lack of visibility (and the other performers also had restricted movement and vision, of course). We had to be very careful, talk to the stunt coordinator, etc.

Eating the frog was also tricky. Gunk in the mouth meant that by the second take the rubber frog was really slippery to hold. To give you an idea of what we were doing in there – Using my right hand I had to tip the head forward, allowing the radio-controlled eyes to look down, then the frog was put in my left hand (out of shot) and I brought it up to the mouth, while leveling the head. At the same time, Dave was opening the mouth. I dropped the frog in and Dave started chewing, while my right hand let go of the head, and slid into the tongue, to lick the lips! All good fun!

John Coppinger: The key point about Jabba was his size and complexity - I don't think anyone had attempted such a large and complex puppet before; certainly not one operated by up to eight people. So almost every aspect of his construction involved R&D, including materials and in particular the foam latex skin. Tom McLaughlin came up with new chemistry that allowed us to use fibreglass moulds, inject the foam with giant syringes (made from drainage pipes) and stack and store the filled moulds for cooking in one giant batch.

His tail had a net woven from heavy fishing line to support the thin foam and allow it to bend with subtle folds. This was made by Mike Osborne over many days; woven over a pattern drawn onto a foam polystyrene cone.

His belly had to be huge and heavy, but how were the guys inside going to move that? I think it was Mike Osborne again, who suggested an air-bag. It looked massively heavy, wobbled realistically but was really light. So, a win / win situation.

The tail mechanism was a twin, three cable rig that allowed the tail to twist and spiral, rowed beautifully by Mike Edmonds! It also had a series of motor-driven cams, between the belly and the ten foot tip. Mike had a foot operated accelerator for this 'writhing' section.

The eyes had oval vac-formed acrylic shells, made to my pattern by the Elstree vac-form shop, and complex internal mechs driven by radio-controlled servos. I think this was a relatively new approach too. They also had foam latex layers inside that moved when the inner eye slit was operated.

Once Jabba was finished and tested in the workshop we had to plan how to move and install him onto the moving throne base on set. This was quite high up on a rostrum. He also had to be dismantled and moved to the bedchamber set and later to the sail barge set. For both of those we fitted a simpler internal tail volume, made of segments of foam polystyrene that could curl up tighter than the cable version. This simpler tail was flickered and thrashed (when he died) with fishing line strung from poles (i.e. a giant string puppet).

The main problem with Jabba was the deadline - Because of the R&D involved we worked 80 hour weeks, rising to several 120 hour weeks; simply because we were testing and trying until we found solutions that worked. I'm very grateful to Stuart for understanding this and covering our backs. I guess he'd had some experience of this during his own career! Animatronics was a frontier then and that was exciting - Something I missed later, even if I didn't miss the mad hours!

I probably mentioned before that we asked Richard Marquand to speak directly to Jabba rather than any one of us. He developed the habit of going up to tell Jabba what was required for each scene. I'm still not sure if he was joking, playing to the audience, or thought Jabba could actually see him!

Eating the frog was also tricky. Gunk in the mouth meant that by the second take the rubber frog was really slippery to hold. To give you an idea of what we were doing in there – Using my right hand I had to tip the head forward, allowing the radio-controlled eyes to look down, then the frog was put in my left hand (out of shot) and I brought it up to the mouth, while leveling the head. At the same time, Dave was opening the mouth. I dropped the frog in and Dave started chewing, while my right hand let go of the head, and slid into the tongue, to lick the lips! All good fun!

"I don't think anyone had attempted such a large and complex puppet before."

John Coppinger: The key point about Jabba was his size and complexity - I don't think anyone had attempted such a large and complex puppet before; certainly not one operated by up to eight people. So almost every aspect of his construction involved R&D, including materials and in particular the foam latex skin. Tom McLaughlin came up with new chemistry that allowed us to use fibreglass moulds, inject the foam with giant syringes (made from drainage pipes) and stack and store the filled moulds for cooking in one giant batch.

His tail had a net woven from heavy fishing line to support the thin foam and allow it to bend with subtle folds. This was made by Mike Osborne over many days; woven over a pattern drawn onto a foam polystyrene cone.

His belly had to be huge and heavy, but how were the guys inside going to move that? I think it was Mike Osborne again, who suggested an air-bag. It looked massively heavy, wobbled realistically but was really light. So, a win / win situation.

The tail mechanism was a twin, three cable rig that allowed the tail to twist and spiral, rowed beautifully by Mike Edmonds! It also had a series of motor-driven cams, between the belly and the ten foot tip. Mike had a foot operated accelerator for this 'writhing' section.

The eyes had oval vac-formed acrylic shells, made to my pattern by the Elstree vac-form shop, and complex internal mechs driven by radio-controlled servos. I think this was a relatively new approach too. They also had foam latex layers inside that moved when the inner eye slit was operated.

Once Jabba was finished and tested in the workshop we had to plan how to move and install him onto the moving throne base on set. This was quite high up on a rostrum. He also had to be dismantled and moved to the bedchamber set and later to the sail barge set. For both of those we fitted a simpler internal tail volume, made of segments of foam polystyrene that could curl up tighter than the cable version. This simpler tail was flickered and thrashed (when he died) with fishing line strung from poles (i.e. a giant string puppet).

The main problem with Jabba was the deadline - Because of the R&D involved we worked 80 hour weeks, rising to several 120 hour weeks; simply because we were testing and trying until we found solutions that worked. I'm very grateful to Stuart for understanding this and covering our backs. I guess he'd had some experience of this during his own career! Animatronics was a frontier then and that was exciting - Something I missed later, even if I didn't miss the mad hours!

I probably mentioned before that we asked Richard Marquand to speak directly to Jabba rather than any one of us. He developed the habit of going up to tell Jabba what was required for each scene. I'm still not sure if he was joking, playing to the audience, or thought Jabba could actually see him!

Echo Base News: How do you feel about Jabba's switch to CGI in later films, and about CGI in general?

John Coppinger: My dream, when asked to work on The Phantom Menace was to come back fifteen years later and sculpt Jabba as a boy. But it wasn't to be! I think most agree that the CGI Jabba, in the re-worked film, is pretty dire. But it was a brave, if foolish, attempt to stretch the boundaries. CGI at that point wasn't up to moving a large animal body and/or capturing the subtleties of facial expressions. Look at what Peter Jackson could do with King Kong, a real love story between the ape and the lady, and maybe they should have waited a few years!

My first real brush with the CGI question came with my high-rolling days at the start of Return to Oz. When the art department set up there was only Norman Reynolds (Production Designer), Bruce Sharman (Producer), a few folks in the office and me. I said something to Bruce about computers for initial design work being possible in the near future from reading New Scientist and Flight International (military simulators). Bruce said "buy a computer then.” I think top of the range then was a Vax-750 at around $5 million.

But all too quickly that level of computing power was available to production companies, and later in everyone's home. Luckily the film industry is a conservative animal at its core, so we lived another ten years at least with making ‘real’ creatures and costumes.

In the early 90’s I was working at Jim Henson’s Creature Shop and seriously considered trying to get involved with their CGI department. At that time they were writing their own software, to control virtual puppets via modified, conventional hand controls. At some point the secrecy was relaxed and I was able to have a go. Very strange then to see an 'on-screen' character responding to my real world input. In the end I went downstairs, stuck my arm in a bag of clay, and realized I preferred to stay in the Stone Age! I don't regret that, and I love what computers can do; I've even built one, but don't ask me what's in there now!

In the early 90’s I was working at Jim Henson’s Creature Shop and seriously considered trying to get involved with their CGI department. At that time they were writing their own software, to control virtual puppets via modified, conventional hand controls. At some point the secrecy was relaxed and I was able to have a go. Very strange then to see an 'on-screen' character responding to my real world input. In the end I went downstairs, stuck my arm in a bag of clay, and realized I preferred to stay in the Stone Age! I don't regret that, and I love what computers can do; I've even built one, but don't ask me what's in there now!

Well at this point I start to wax metaphysical. What interests me is how we and the audience suspend our disbelief. I always assumed I did that with reference to classic string puppets and early attempts at Animatronics, whereas a younger generation did so with reference to computer games. Now I'm not so sure, and that's where the metaphysical comes in. I think we can still tell if a scene in a film is ‘real,’ i.e. at some point in its making there were human witnesses. My standard illustration is the first sight of Earth in space, by the crew of Apollo 8 (Christmas 1968). Until then most of us knew the Earth was in space but no one had actually been out there to confirm it.

We may be close to the point where CGI is so good we really can't tell the difference; then virtual reality and real reality will start mixing in really interesting ways! I guess in the end it's like fiberglass for me; don't much like using it but love what it does. Look at relatively low budget TV and especially adverts. The effects are just astonishing. Once directors and art departments fall completely out of love with CGI, and start using it as an appropriate tool, it will just be the latest, best way we can tell each other stories.

Two directors come to mind who understand CGI as a great tool, no more, no less: Peter Jackson and Luc Besson (The Fifth Element).

We may be close to the point where CGI is so good we really can't tell the difference; then virtual reality and real reality will start mixing in really interesting ways! I guess in the end it's like fiberglass for me; don't much like using it but love what it does. Look at relatively low budget TV and especially adverts. The effects are just astonishing. Once directors and art departments fall completely out of love with CGI, and start using it as an appropriate tool, it will just be the latest, best way we can tell each other stories.

Two directors come to mind who understand CGI as a great tool, no more, no less: Peter Jackson and Luc Besson (The Fifth Element).

"We may be close to the point where CGI is so good we really can't tell the difference; then virtual reality and real reality will start mixing in really interesting ways!"

Toby Philpott: Let’s face it, all films are artificial, but an artistic choice still has to be made between fantastic images (like Warner Brothers and Disney cartoons, and now Pixar) and ‘looking like real life.’ It’s extremely expensive to mix the two (look at Roger Rabbit). So in The Phantom Menace Jabba looks reasonably good (compared to the horrible version they added to the early footage with Harrison Ford) but he is on a balcony, not interacting with humans, as we could.

I guess it does depend on your eye, too, as I don’t play computer games, so that modern ‘hyper-real’ look doesn’t appeal to me. It looks like animation when Clone armies march...but perhaps to gamers it has become invisible. Generations move on. For instance, the stop-frame animation of Ray Harryhausen, exhilarating to one generation, now looks artificial.

I guess it does depend on your eye, too, as I don’t play computer games, so that modern ‘hyper-real’ look doesn’t appeal to me. It looks like animation when Clone armies march...but perhaps to gamers it has become invisible. Generations move on. For instance, the stop-frame animation of Ray Harryhausen, exhilarating to one generation, now looks artificial.

As I say, any style can be valid as a tool in the filmmaker’s equipment, but it still has to be done well, to satisfy an audience. If you don’t dwell on CGI effects they can work really well (the velociraptors fooled my eye in Jurassic Park

So perhaps the nostalgia I hear about from older fans, for the Original Trilogy, arises from the fact that everything in them ‘looks real,’ because most of what you see was really there...and unlike green screen, for instance, I think it made it easier and more fun for the actors, too.

So perhaps the nostalgia I hear about from older fans, for the Original Trilogy, arises from the fact that everything in them ‘looks real,’ because most of what you see was really there...and unlike green screen, for instance, I think it made it easier and more fun for the actors, too.

Dave Barclay: I wasn't a fan of the first switch to CGI. Not surprisingly so as I was out of work...but I didn't care for the sculpture and changes they added. I thought John's original sculpt was brilliant, so they did have a hard act to follow. But I understand the movie industry’s' need to continue developing and pushing new technology. Indeed it was that desire to push the envelope that made A New Hope so spectacular.

Generally I see CGI as a great movie tool. There have been some wonderful CG characters and performances (who doesn't love Toy Story? and Gollum?) so with the right blend of character and performance, the potential is great. However, few CG characters capture the inherent tactile sense of actually being in our world (when Spiderman changed from the real Tobey Maguire to the CG stunt double, it pulled me out of the movie).

I'm developing new technology to allow the performers and puppeteers to use their performance skills in a hybrid performance capture system, which is both exciting and ridiculously expensive. Ah, the joys of progress.

Generally I see CGI as a great movie tool. There have been some wonderful CG characters and performances (who doesn't love Toy Story? and Gollum?) so with the right blend of character and performance, the potential is great. However, few CG characters capture the inherent tactile sense of actually being in our world (when Spiderman changed from the real Tobey Maguire to the CG stunt double, it pulled me out of the movie).

I'm developing new technology to allow the performers and puppeteers to use their performance skills in a hybrid performance capture system, which is both exciting and ridiculously expensive. Ah, the joys of progress.

(l to r) John Coppinger, Mike Edmonds, Dave Barclay, and Toby Philpott with Jabba at a convention.

Echo Base News: What has made Jabba such a popular character nearly thirty years later?

Toby Philpott: This is just a personal opinion, but I don’t think too many people really want to play the part of a sensible, ‘good’, clean-living hero, and only a certain special kind of person wants to manifest the incarnations of total evil…Rogues, pirates, smugglers, gangsters and other amoral people seem the most fun to pretend to be. Neither Han Solo nor Jabba take part in the grand battle of good and evil. They are both outsiders, opportunists, ‘bad boys.’ So although Han Solo is sexy and funny and poor, and Jabba is repulsive, scary, rich and decadent, perhaps they both appeal to the wicked and mischievous aspects of ourselves. Think Robin Hood, Pirates of the Caribbean , The Godfather, Bruce Willis, Orson Welles…

John Coppinger: I guess he's a lovable rogue at base; the character who stands in for our less pleasant sides and yet can be forgiven. We're just watching the Babylon

We were lucky to work on such a major (in all senses!) character. Jabba is like the host of a nightclub where the audience has been let in by the bouncer on the door, and so feels they are part of the ‘in crowd.’ It's also unusual to work on a creature/character that has so much screen time and this might be another part of the old slug gangster's appeal; definitely a film within a film and a party atmosphere!

We were lucky to work on such a major (in all senses!) character. Jabba is like the host of a nightclub where the audience has been let in by the bouncer on the door, and so feels they are part of the ‘in crowd.’ It's also unusual to work on a creature/character that has so much screen time and this might be another part of the old slug gangster's appeal; definitely a film within a film and a party atmosphere!

Toby Philpott: People do sometimes query my theory of ‘loveable rogue’ by pointing out that he kills people. I can only answer that he doesn't kill Hutts, just lesser lifeforms like humans and Twi'leks. I don't think many humans find themselves in a position to consider killing (or even eating) other species as evil. Except vegetarians and vegans, perhaps. “Pass the Klatooine paddy frogs!”

Dave Barclay: He is designed to be evil and in every way succeeds in delivering that. Throughout the entire Jabba team, from Stuart to Phil Tippett who designed him, Jabba was a culmination and collaboration of the greatest talents of the movie industry at that time. And his legacy lives on, even if his foam latex skin has crumbled to dust. Long live Jabba.

Interview by Chris Wermeskerch and David Delgado.

We hope you enjoyed our two-part Jabba interview. It's certainly quite a detailed account of everything you ever wanted to know about Jabba, from the people who brought him to life! We'd like to thank John, Dave and Toby for taking the time to share all these details with us.

Interview by Chris Wermeskerch and David Delgado.

We hope you enjoyed our two-part Jabba interview. It's certainly quite a detailed account of everything you ever wanted to know about Jabba, from the people who brought him to life! We'd like to thank John, Dave and Toby for taking the time to share all these details with us.

awesome,

ReplyDeletethank you so much for sharing such an wesome

blog..

really i like your site.

i enjoyed...

acrylic podiums